Last updated: June 04, 2012

About the International HapMap Project

About the International HapMap Project

- What was the International HapMap Project?

- Why is it important to study genetic variation?

- What are single nucleotide variations (SNPs), alleles and genotypes?

- What is a haplotype?

- What populations were sampled?

- How did the project address ethical issues?

- What was the project's scientific strategy?

- What are the policies concerning data access and intellectual property?

What was the International HapMap Project?

The goal of the International HapMap Project was to develop a haplotype map of the human genome. Often referred to as the HapMap, it describes the common patterns of human genetic variation.

The HapMap provides a key resource for researchers to use to find genes affecting health, disease and responses to drugs and environmental factors. The information produced by the project is now freely available in public databases to researchers around the world.

The International HapMap Project officially started with a meeting, held from Oct. 27 to 29, 2002, and achieved its goal of completing the map within three years. The project was a collaboration among researchers at academic centers, non-profit biomedical research groups and private companies in Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada, China, Nigeria and the United States. A list of participating and funding institutions is available at: http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/groups.html.

Why is it important to study genetic variation?

Most common diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, stroke, depression and asthma, are affected by many genes and environmental factors. Although any two unrelated people share about 99.9 percent of their DNA sequences, the remaining 0.1 percent is important because it contains the genetic variants that influence how people differ in their risk of disease or response to drugs.

Discovering the DNA sequence variants that contribute to disease risk offers one of the best opportunities for understanding the complex causes of many common diseases in humans.

What are single nucleotide variations (SNPs), alleles and genotypes?

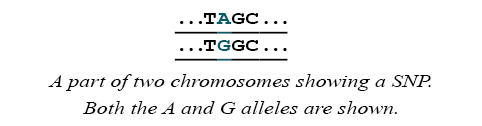

Sites in the genome where the DNA sequences of many individuals vary by a single base are called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). For example, some people may have a chromosome with an A at a particular site where others have a chromosome with a G. Each form is called an allele.

Each person has two copies of all chromosomes, except for the sex chromosomes. The set of alleles that a person has is called a genotype. The term genotype can refer to the SNP alleles that a person has at a particular SNP, or for many SNPs across the genome. A method that discovers what genotype a person has is called genotyping.

What is a haplotype?

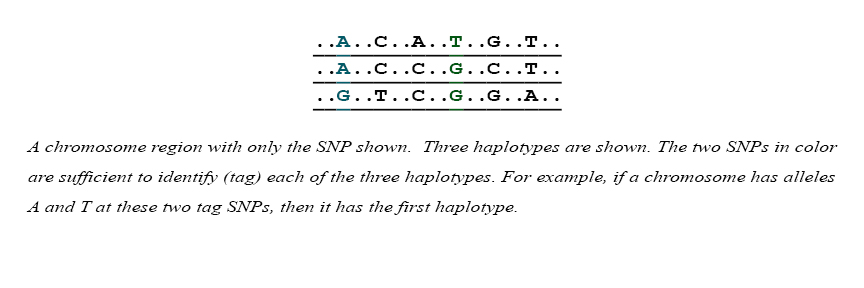

About 10 million SNPs exist in human populations for which the rarer SNP allele has a frequency of at least 1 percent. Alleles of SNPs that are close together tend to be inherited together. A set of associated SNP alleles in a region of a chromosome is called a haplotype. Most chromosome regions have only a few common haplotypes, which account for most of the variation from person to person in a population. A chromosome region may contain many SNPs, but researchers can use only a few "tag" SNPs to obtain most of the information on the pattern of genetic variation in the region.

The HapMap describes the common patterns of genetic variation in humans. It includes the chromosome regions with sets of strongly associated SNPs, the haplotypes in those regions and the SNPs that tag those haplotypes. It also notes the chromosome regions where associations among SNPs are weak.

Researchers trying to discover the genes that affect a disease, such as diabetes, will compare a group of people with the disease to a group without the disease. Chromosome regions where the two groups differ in the haplotype frequencies might contain genes affecting the disease. Theoretically, researchers could look for these regions by genotyping 10 million SNPs. However, methods to do this are currently too expensive. The HapMap identifies the 250,000 to 500,000 tag SNPs that provide almost as much mapping information as all 10 million SNPs.

What populations were sampled?

Most of the common haplotypes occur in all human populations. However, their frequencies differ among populations. Therefore, data from several populations were needed to choose tag SNPs. Pilot studies found sufficient differences in haplotype frequencies among population samples from Nigeria (Yoruba), Japan, China and the United States (Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe) to warrant developing the HapMap with large-scale analysis of haplotypes in these populations.

The HapMap developed from information obtained from these populations should be useful for all populations in the world. However, to assess how much more information would be gained by including other populations, researchers will examine haplotypes in a set of chromosome regions in samples from several additional populations.

Specifically, the DNA samples for the Phase I HapMap came from a total of 269 people: from the Yoruba people in Ibadan, Nigeria (30 both-parent-and-adult-child trios), the Japanese in Tokyo (45 unrelated individuals), the Han Chinese in Beijing (45 unrelated individuals) and the Utah residents of northern and western European ancestry (30 trios). These numbers of samples enabled the project to find almost all haplotypes with frequencies of 5 percent or higher.

All of the new samples collected for the project were obtained with protocols approved by the appropriate ethics committees, after culturally appropriate processes of community engagement or public consultation and individual informed consent. The community engagement process was designed to identify and attempt to respond to culturally specific concerns and give participating communities input into the informed consent and sample collection processes.

How did project address ethical issues?

The project raises a number of ethical issues. Since the samples included no personal identifiers, the privacy risks to individual donors are minimal. However, each sample was labeled by population to allow researchers to choose tag SNPs that are most useful for each future study population. The tag SNPs were chosen based on the haplotype frequencies. The tag SNPs for some regions might differ among populations if the haplotype frequencies in those regions were considerably different among populations. Thus, the SNP and haplotype frequencies for each population will be calculated, allowing comparisons. This could raise risks of group stigmatization or discrimination, if a higher frequency of a disease-associated variant were found in a population and risks associated with that variant were over-generalized to all or most members of the population.

Another potential concern is that the inclusion of populations based on ancestral geography could result in categories such as "race," which are largely socially constructed, being incorrectly viewed as precise and highly meaningful biological constructs. The project undertook the community consultations to understand community concerns about such issues.

What was the project's scientific strategy?

To develop the HapMap, the samples were genotyped for 3 million SNPs across the human genome. When the Project started, 2.6 million SNPs were in the public database dbSNP [ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]. However, many chromosome regions had too few SNPs, and many SNPs were too rare to be useful, so millions of additional SNPs were needed to develop the HapMap. The project discovered another 6 million SNPs.

The genotyping was carried out by 11 centers in Canada, China, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. For Phase I, each center genotyped all the samples for its assigned chromosomes. The centers used six genotyping technologies. The initial Phase I map produced data on 1 million SNPs in the HapMap samples, evenly spaced across the genome. In Phase II, another 2.1 million SNPs were genotyped in the samples. Genotyping quality was assessed by using duplicate samples, by having all centers genotype a standard set of SNPs, by having centers check some of the genotypes produced by other centers, and by comparing overlap data with other projects.

What are the policies concerning data access and intellectual property?

The project released all the data it produced into the public domain, enabling any researcher worldwide to use the information for free.

The project does not include "specific utility" studies to relate genetic variation to particular phenotypes, such as a disease risk or drug response. Participants in the project do not believe that SNP, genotype or haplotype data for which a specific utility has not been generated are appropriately patentable inventions. However, the project's policy does not prevent researchers from applying for patents on SNPs or haplotypes for which they have demonstrated a specific utility, as long as they do not prevent others from obtaining access to project data.