Last updated: September 16, 2011

Researchers Uncover Genetic Clues of Age-Related Dementia

National Human Genome

Research Institute (NHGRI)

www.genome.gov

Researchers Uncover Genetic Clues of Age-Related Dementia

Gene Responsible for Rare Disease May Play Role in Common Disorder

BETHESDA, Md., Sun., July 16, 2006 - Researchers have found that genetic alterations originally identified in people suffering from a rare disease may also be an important risk factor for the second most common form of dementia among the elderly.

BETHESDA, Md., Sun., July 16, 2006 - Researchers have found that genetic alterations originally identified in people suffering from a rare disease may also be an important risk factor for the second most common form of dementia among the elderly.

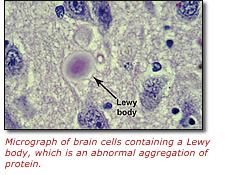

In a study recently published online in the journal Neurology, a group from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia reported that alterations in the gene that codes for an enzyme called glucocerebrosidase (GBA) may contribute to the development of a relatively common neurodegenerative disease known as dementia with Lewy bodies, or DLB. Lewy bodies are abnormal aggregates of protein that develop inside nerve cells in both DLB and Parkinson's disease. Mutations in the GBA gene had previously been identified as the cause of Gaucher disease, a rare, inherited metabolic disorder.

"This work shows how genetic and genomic research involving rare diseases can help unravel the mysteries of more common disorders," said NHGRI Scientific Director Eric Green, M.D., Ph.D., "Knowledge gained from studying rare diseases not only provides insights into specific medical conditions, it also deepens our understanding of normal cell processes and human biology in general."

DLB is the second most common form of age-related dementia, exceeded only by Alzheimer's disease. At least 5 percent of people age 85 and older are thought to have DLB, and the condition accounts for about one-fifth of all cases of dementia. People affected by DLB often show symptoms of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease, but most experts now consider DLB to be a distinct disorder. As is the case for Alzheimer's disease, there currently is no good treatment for DLB.

A research group led by Ellen Sidransky, M.D., a senior investigator in NHGRI's Division of Intramural Research, sequenced DNA from autopsy samples that had been carefully examined and classified by neuropathologists at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Sidransky's group found mutations in the GBA gene in 23 percent of patients with DLB. That rate is nearly 40 times higher than the frequency of GBA mutations in the general population.

"Our findings are particularly significant because this is among the first examples of a genetic change associated with dementia with Lewy bodies. This discovery will serve to advance our understanding of the mechanisms underlying this devastating disease," said Dr. Sidransky, who is also acting chief of NHGRI's Medical Genetics Branch.Until recently, most research on GBA focused on Gaucher disease, a rare, inherited metabolic disorder in which harmful quantities of a fatty substance, called glucocerebroside, accumulate in the spleen, liver, lungs, bone marrow and, in some cases, the brain. All people with Gaucher disease have a deficiency of the GBA enzyme, which is involved in the breakdown and recycling of glucocerebroside.

Over the past few years, Dr. Sidransky's lab and other research groups have uncovered data suggesting that GBA alterations may also be a risk factor for the development of symptoms that resemble those seen in Parkinson's disease. The latest findings add DLB to the list of disorders in which the GBA gene may play a role. People with Gaucher disease have two mutated copies of the GBA gene, while the DLB patients with GBA alterations have one mutated copy and one normal copy.

"This serves as an example of how a genetic alteration may lead to a key enzyme taking on a totally different role from its primary function, contributing to a common, complex disorder," said Ozlem Goker-Alpan, M.D., a clinical fellow in Dr. Sidransky's lab and the first author of the study.

Specifically, the NHGRI-led group examined the GBA gene in autopsy specimens from 75 patients who had been diagnosed with a class of neurodegenerative disorders known as synucleinopathies, which are characterized by abnormal aggregates of a protein called alpha-synuclein within brain and other neural cells. The three synucleinopathies examined in the study were DLB, Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy.

Researchers found GBA mutations in the brain tissue of eight of the 35 cases of DLB. Only one of 28 patients with "classic" Parkinson's disease had a GBA alteration, while no mutations were found among the 12 patients with multiple system atrophy.

The results may offer intriguing new avenues for exploring the basic causes of a complex disease at the cellular level. However, the researchers emphasized that more work and larger groups of samples are needed to confirm these associations and determine exactly how GBA alterations may contribute to the accumulation of alpha-synuclein in neuronal cells.

To download microphotographs of brain cells containing Lewy bodies, go to www.genome.gov/dmd/img.cfm?node=Photos/Technology/Cells and biological pathways&id=79193 and www.genome.gov/dmd/img.cfm?node=Photos/Technology/Cells and biological pathways&id=79194.

The NHGRI Division of Intramural Research develops and implements technology to understand, diagnose and treat genomic and genetic diseases. Additional information about NHGRI can be found at www.genome.gov.

The National Institutes of Health - The Nation's Medical Research Agency - includes 27 institutes and centers, and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It is the primary federal agency for conducting and supporting basic, clinical and translational medical research, and it investigates the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH, visit www.nih.gov.

Editor's Note: For information on another recent genetic finding related to dementia, contact Linda Joy at the National Institute on Aging, (301) 496-1752, ljoy@nia.nih.gov.

Contact:

Geoff Spencer

NHGRI

(301) 402-0911

spencerg@mail.nih.gov