Last updated: February 04, 2012

Luminaries Shed Light on Genomics' Bright Future

Luminaries Shed Light on Genomics' Bright Future

By Jeannine Mjoseth

NHGRI Staff Writer

|

Luminaries of genomic research described their vision for the field's future to a standing-room-only crowd at the National Institutes of Health's Natcher Conference Center on Feb. 11, 2011. Hosted by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), the symposium marked the release of a new strategic vision for genomics published in the Feb. 10 issue of the journal Nature.

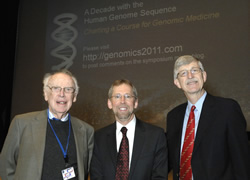

Among those joining NHGRI Director Eric Green, M.D., Ph.D., for the day-long symposium, A Decade With the Human Genome Sequence: Charting a Course for Genomic Medicine, were Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D., NIH director and former NHGRI director, NHGRI founding director James Watson, Ph.D., who won the Nobel Prize for co-discovering the double helix structure of DNA in 1953, Eric Lander, Ph.D, founder of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and Maynard Olson, Ph.D., professor emeritus of genome sciences and medicine at the University of Washington.

|

"We're celebrating the day by marveling at the past and anticipating the future," Dr. Green said. "Science changed when we generated that first sequence of the human genome and what a remarkable decade it has been since." Dr. Green noted that the strategic plan was released on the 10th anniversary of the initial sequence and analysis of the draft human genome sequence in Nature magazine.

Dr. Collins remarked that, in the 10 years since release of the sequence, researchers have discovered the molecular basis of 4,000 disorders and 1,000 genetic variations that make a small contribution to common complex diseases and point towards potential therapeutic targets.

|

Dr. Collins, who led the Human Genome Project from 1993 until its completion in 2003, spoke about the importance of building "the bridge between basic discoveries and new therapeutics." One way to do this, he said, is through NIH's proposed National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The center would focus on accelerating the development and delivery of new, more effective therapeutics and serve as a resource for the entire translational science community as they move promising products through the development pipeline.

Dr. Maynard Olson, professor emeritus of genome sciences and medicine at the University of Washington, also commented on the need to integrate information that can now be readily gathered into the real world of medicine.

"The potential is finally here to move genomics out into the real world," Olson said. "I guarantee if you start getting molecular data into health records and not just into some artificial study ... there will be a tremendous dialogue between the clinical community, patients and society at large."

Research on the ethical, legal and social implications (ELSI) of genomic research and medicine will be crucial to this dialogue and to genomics' acceptance into mainstream medical care, said Dr. Amy McGuire, associate professor of medicine and medical ethics and associate director of research for the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. McGuire noted she had worked on ethical, legal and social issues that arose in 2007 when Dr. Watson's personal genome was sequenced and analyzed at the Baylor College of Medicine.

|

"Researchers at 454 Life Sciences and Baylor College of Medicine were very conscious and conscientious about the ethical, legal and social issues that came up during the project and the project's broader implications for how we integrated whole genome sequences into our research practice and clinical care," she said. The close integration between the scientists and ELSI researchers resulted in better research on both sides, she noted.

Dr. Watson said that having his genome sequenced provided him key information on how he metabolized certain drugs like beta-blockers, a heart pressure medication. As a result, doctors advised Dr. Watson to only take one pill per week rather than one daily.

"That was an extremely useful fact, which I wouldn't have known without having my genome sequenced," he said. He declined the offer to know his genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease, which afflicted his grandmother.

"A tremendous amount about medicine has been cracked open, but it's just barely a start, most of what we need to know about the genome still lies before us," said Dr. Eric Lander, director of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Mass. Dr. Lander is well known for advocating large DNA sequencing projects such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) a comprehensive effort to understand the genomic basis of cancer. Referring to the recently completed 1,000 genomes project, he recommended a "1 million genomes project" to provide a truly comprehensive resource on human genetic variation.

Videos of each talk are available at NHGRI's YouTube channel, GenomeTV. More information about the symposium, including an agenda and biographies of the speakers, is available at: A Decade with the Human Genome Sequence: Charting a Course for Genomic Medicine.

Last Reviewed: February 4, 2012