Last updated: July 30, 2012

NIH researchers use brain imaging to understand genetic link between Parkinson's and a rare disease

NIH researchers use brain imaging to understand genetic link between Parkinson's and a rare disease

Role of Gaucher disease-gene alterations is clarified by six-year study

By Steven Benowitz

Special to NHGRI

|

A rare metabolic disorder is helping researchers at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) uncover new clues about the biology underlying Parkinson's disease. The results of their six-year study, published online in the July 30, 2012, issue of the journal Brain, may explain how people with alterations in the gene involved in Gaucher disease are more likely to develop Parkinson's — and provide a window to potential inner workings of Parkinson's itself.

"It's important to understand why having a mutation in this gene predisposes someone to Parkinson's," said Ellen Sidransky, M.D., co-senior author and senior investigator in NHGRI's Medical Genetics Branch. "Clinically, we've seen that people with Gaucher mutations are at increased risk of developing Parkinson's and have noted that these patients can have earlier and more progressive symptoms, but these new findings provide biological evidence to support those differences."

Gaucher disease is an inherited disease caused by mutations in the GBA gene, which codes for the enzyme glucocerebrosidase, which breaks down fatty molecules in the cell for disposal. When this housekeeping enzyme doesn't work properly, the fatty molecules pile up and ultimately can damage the spleen, liver, bones and other organs. The most severe form results in severebrain damage and early death. People affected by Gaucher disease inherit two defective gene copies; those who carry only one gene mutation do not have the disease.

Parkinson's disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects about 1.5 million Americans, causing tremors and motor impairment. It results from a combination of age, environmental factors and genetic susceptibility. Both patients with Gaucher disease and those who carry one mutation in this gene are at increased risk for developing Parkinson's.

In 2009, Dr. Sidransky and her team coordinated a large, international study of the association between the two disorders. The results, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, showed that those with Gaucher-related gene mutations had a five-times greater risk of developing Parkinson's. "We didn't expect this metabolic disorder to be linked to an unrelated neurodegenerative disorder, and we've been working to understand the mechanisms involved and their implications," Dr. Sidransky said.

Previous research showed that people with GBA mutations and Parkinson's tend to develop the disease earlier and have more cognitive difficulties than generally seen in Parkinson's. In the current study, the researchers set out to determine if the brain biology of GBA-associated Parkinson's is different from that observed in others with Parkinson's disease.

Investigators looked at 107 study participants divided into four groups: people with both diseases; those with Parkinson's and no Gaucher mutations; people with Gaucher disease and a family history of Parkinson's; and healthy GBA-mutation carriers with a family history of Parkinson's. Each test group was matched with a comparison group of healthy people who were examined the same way.

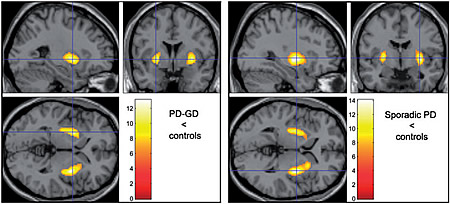

The researchers used two types of an imaging technique called positron emission tomography (PET) to study the brains of participants. One type measured the amount and distribution of dopamine, an important message-carrying brain chemical lacking in people with Parkinson's. The second technique gauged blood flow in the brain, which reflects brain function.

The researchers found that people with Parkinson's disease — both those with and those without Gaucher disease — had a similar reduction in dopamine levels, indicating damage to certain nerve cells in the brain in both groups. "We're fairly early along in understanding how mutations in the GBA gene predispose people to Parkinson's," said Karen Berman, M.D., co-senior author and chief of NIMH's Clinical Brain Disorders Branch. "We now need to investigate the mechanisms by which mutations in this gene may affect dopamine function and the health of dopamine neurons in the brain."

They also found striking differences in blood flow, which was significantly reduced in the people with GBA mutations. They saw this blood flow reduction in specific brain regions where people with different forms of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, are affected.

"This different blood flow distribution has been seen in other disorders that involve cognitive impairment," Dr. Sidransky said. "This provides biologic confirmation of our clinical impression of problems with cognition in some patients with GBA-associated Parkinson's disease. This observation may help us to better understand the causes of dementia that can develop in Parkinson's disease and related disorders and could ultimately lead to strategies to target these problems."

The investigators also examined dopamine distribution and brain blood flow/brain activity in the two groups thought be at high-risk for developing Parkinson's — people with a family history of Parkinson's who either have Gaucher disease or are healthy yet carry a GBA mutation. They looked at the PET scans to identify any significant, early brain changes compared to people in the study control groups. Among seven mutation carriers and 14 patients with Gaucher without Parkinson's, only two had reduced dopamine levels.

Dr. Sidransky said that while long-term follow-up is needed to see if any of these people develop Parkinson's, the observation that most of the patients with GBA mutations didn't have early signs of Parkinson's may be reassuring to those considered at risk.

"Not everyone with GBA alterations will develop Parkinson's," Dr. Sidransky said. "Identifying an early marker associated with disease may show us who might go on to develop Parkinson's, and help identify a population that could benefit from pre-symptomatic management. In addition, discovering why other at-risk individuals do not develop Parkinson's disease may also help us to understand factors that protect people from developing this disease."

The researchers plan to continue to follow people in their study with GBA mutations and a family history of Parkinson's to monitor their dopamine levels and cerebral blood flow to see whether they develop Gaucher disease. The researchers also will assess whether these clinical data might predict which patients will eventually develop Parkinson's disease.

Posted: July 30, 2012