The Big Picture

- Human DNA sequences (that is, our genomes) are more than 99.9% identical among people.

- The 0.1% genomic differences come from variations among the nearly 3 billion bases (or “letters”) in our DNA; sometimes these variations can influence our chances of developing a disease.

- So far, most people who have given permission for their DNA to be used for research are from European ancestry, making many populations from across the globe inadequately represented in genomics research.

- The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) is working to enhance the participation of individuals from groups that have historically not participated in genomics research, thereby improving our knowledge of human genomic variation and genomic information for all populations.

What makes human genomes diverse?

While humans are similar in most ways, our biological processes make each of us unique. Many aspects of those processes are encoded in our DNA, which is based on the sequence of the four letters of life — A, C, G, and T. The dissimilarities among human genomes, referred to as variants, come from differences in our DNA sequences.

The human genome is more than 3 billion letters long, which means that a variant could reside at any place among those letters. These variants occur at different frequencies across different human populations; some are rare and unique to specific families, while others are common and found across populations.

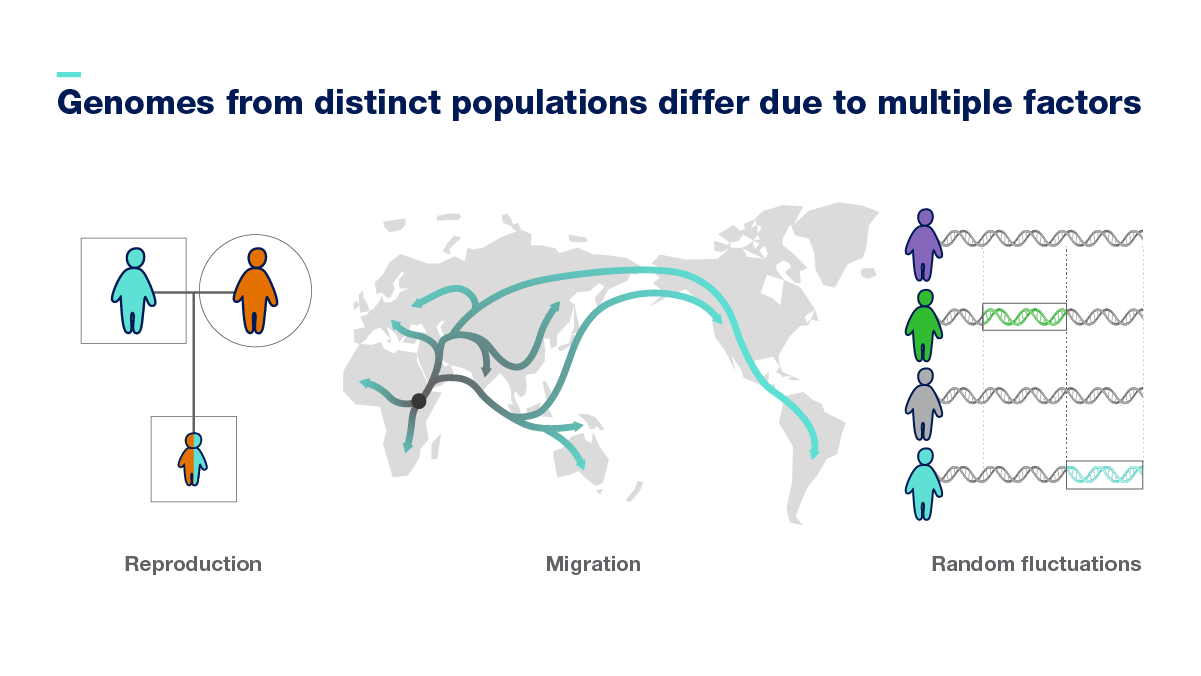

Genomes from distinct populations differ due to multiple factors, including who people decide to reproduce with, as well as human migration patterns. Also, in specific populations, certain variants became widespread as they provided an advantage that helped them adapt to environmental changes.

Factors displayed in the graphic include: reproduction, migration and random fluctuations.

How does studying all human genomes improve health outcomes?

Every human has some baseline genetic risk of developing a given disease. Extensive research has been performed to both understand and learn how to respond to these risks. In some cases, the same variant consistently causes a disease (e.g., Huntington's disease and cystic fibrosis), but this might not be the case for more complex diseases (e.g., coronary artery disease, obesity, cancer and Alzheimer’s disease).

By including populations that reflect the full spectrum of human populations in genomic studies, researchers can identify genomic variants associated with various health outcomes at the individual and population levels. This way, researchers can better define a person's risk of developing a specific disease and design a clinical management strategy that is tailored to the individual. In addition, they can pursue genomic medicine strategies that benefit specific populations.

Why has enhancing participation in genomics research been a difficult task?

Increasing the participation of all populations in genomics research requires an investment of both resources and time to intentionally establish trusting and respectful long-term relationships between communities and researchers. To ensure that genomics research is both equally beneficial and comprehensive, it is crucial for the genomics research workforce to reflect the communities that the research is intended to serve.

In the past, both inaccessible and insufficient communication left some research participants unclear about the benefits of their participation and how their data would be used after the studies concluded. To overcome this, researchers must seek to understand people’s reasons for not participating in genomic studies and to communicate with participants in a more accessible manner. This can take additional time, effort and resources, which may discourage some researchers from including these important populations in their studies. However, such exclusion can lead to notable gaps in scientific understanding and potentially reenforce existing disparities in genomics research.

Last updated: February 24, 2025