The disease, 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, also known as DiGeorge syndrome and velocardiofacial syndrome, affects from 1 in 3,000 to 1 in 6,000 children. Because the disease results in multiple defects throughout the body, including cleft palate, heart defects, a characteristic facial appearance and learning problems, healthcare providers often can't pinpoint the disease, especially in diverse populations.

The goal of the study, published March 23, 2017, in the American Journal of Medical Genetics, is to help healthcare providers better recognize and diagnose DiGeorge syndrome, deliver critical, early interventions and provide better medical care.

"Human malformation syndromes appear different in different parts of the world," said Paul Kruszka, M.D., M.P.H., a medical geneticist in NHGRI's Medical Genetics Branch. "Even experienced clinicians have difficulty diagnosing genetic syndromes in non-European populations."

The researchers studied the clinical information of 106 participants and photographs of 101 participants with the disease from 11 countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The appearance of someone with the disease varied widely across the groups.

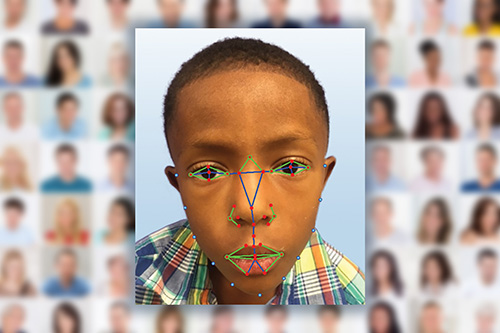

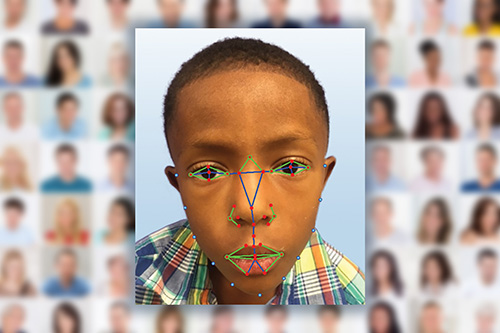

Using facial analysis technology, the researchers compared a group of 156 Caucasians, Africans, Asians and Latin Americans with the disease to people without the disease. Based on 126 individual facial features, researchers made correct diagnoses for all ethnic groups 96.6 percent of the time.

Marius George Linguraru, D.Phil., M.A., M.B., an investigator at the Sheikh Zayed Institute for Pediatric Surgical Innovation at Children's National Health System in Washington, D.C., developed the digital facial analysis technology used in the study. Researchers hope to further develop the technology - similar to that used in airports and on Facebook - so that healthcare providers can one day take a cell phone picture of their patient, have it analyzed and receive a diagnosis.

This technology was also very accurate in diagnosing Down syndrome, according to a study published in December 2016. The same team of researchers will next study Noonan syndrome and Williams syndrome, both of which are rare but seen by many clinicians.

DiGeorge syndrome and Down syndrome are now part of the Atlas of Human Malformations in Diverse Populations (www.genome.gov/atlas) launched by NHGRI and its collaborators in September 2016. When completed, the atlas will consist of photos of physical traits of people with many different inherited diseases around the world, including Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, South America and sub-Saharan Africa. In addition to the photos, the atlas will include written descriptions of affected people and will be searchable by phenotype (a person's traits), syndrome, continental region of residence and genomic and molecular diagnosis. Previously, the only available diagnostic atlas featured photos of patients with northern European ancestry, which often does not represent the characteristics of these diseases in patients from other parts of the world.

"Healthcare providers here in the United States as well as those in other countries with fewer resources will be able to use the atlas and the facial recognition software for early diagnoses," said Maximilian Muenke, M.D., atlas co-creator and chief of NHGRI's Medical Genetics Branch. "Early diagnoses means early treatment along with the potential for reducing pain and suffering experienced by these children and their families."