In a May 26 New England Journal of Medicine perspective, Vence L. Bonham, J.D., an investigator with NHGRI's Social and Behavioral Research Branch, and his colleagues, are asking if the precision medicine approach will reduce or eliminate the role that race plays in prescribing drugs and in health care overall.

"We focus on drug therapies because that's where the precision medicine approach to treatment will make the biggest difference, initially," said Mr. Bonham. "Precision medicine is moving us toward individualized care and away from race-based decision-making on what is the best medication for a patient. It doesn't mean that the use of race in medical care will entirely go away, but its role will likely change."

Precision medicine is promoted as a way of eliminating imprecise prescribing practices. This means including in drug studies people from diverse social, racial and ethnic, and ancestral groups who live in a variety of places, social environments and economic circumstances, and from all age groups and health statuses.

"Inclusion of diverse people in longitudinal drug studies will advance knowledge about the similarities and differences in health, disease and drug responses," Mr. Bonham and his colleagues wrote. "It will also provide key information to guide drug selection and dosing." Longitudinal studies are those that are conducted over long periods of time.

Though there's an ongoing debate about using race in prescribing medications, federal agencies, health care organizations, providers and insurers continue to use it in certain circumstances to guide treatment decisions, according to the perspective. A decade ago, for example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first race-based drug for heart failure in self-identified black patients (BiDil). At the time, critics said that race alone is insufficient to determine who can or cannot benefit from a certain drug. The authors also cite 2014 drug guidelines for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for hypertension that recommend using the race of the patient as a factor in treatment decisions.

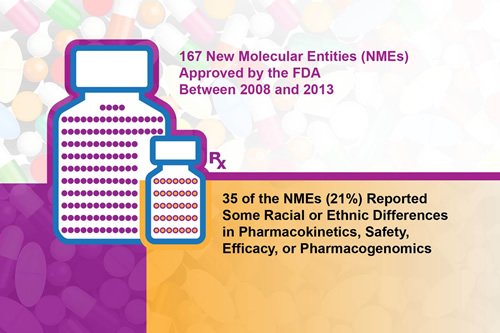

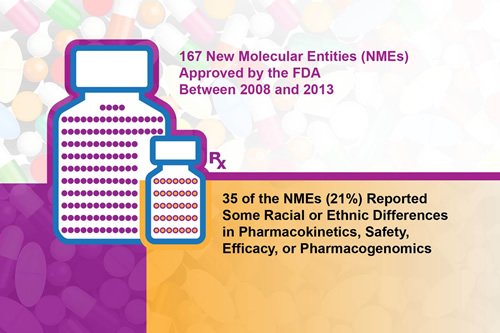

The trend continues: A 2015 review of new drugs approved by FDA between 2008 and 2013, found that one-fifth of the new molecular entities (NMEs) reported "some interracial/ethnic variability with respect to pharmacokinetics, safety, efficacy, dosing or pharmacogenetics."

If a precision medicine approach to health care is to replace the use of race in treatment decisions, certain challenges must be addressed according to the perspective.

The first challenge is the lack of knowledge about similarities and differences in health, disease and drug responses within and between populations. To address this challenge, the National Institutes of Health's Precision Medicine Initiative Working Group has recommended that the Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort Program broadly reflect the diversity of the United States and strive to recruit sufficient numbers of participants from diverse populations to address scientific questions. This will improve understanding of which drugs work and in what doses.

The second challenge is the rising costs of precise drug prescribing. Drugs that work for a small number of people are likely to be more expensive and possibly cost prohibitive for insured people. Also, information that an insurance company requires for coverage of a drug may not be available.

The third challenge is integrating precision medicine into health care systems. Health care providers and the systems in which they work must be trained to use genomic, environmental, lifestyle and social data to guide health care.

"Eventually, precision medicine will revolutionize the utility of race in prescribing medications," said Mr. Bonham. "We have highlighted the importance of genomic knowledge and the precision medicine approach in moving us beyond the use of crude racial and ethnic categories in the care of the individual patient."