Human Genome Project Timeline

Completed in April 2003, the Human Genome Project gave us the ability to read nature's complete genetic blueprint for a human. This interactive timeline lists key moments from the history of the project.

1984-86

Early meetings assess the feasibility of a Human Genome Project. More +

1984-86

In December 1984, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the International Commission for Protection against Environmental Mutagens and Carcinogens (ICPEMC) cosponsor "The Alta Summit," highlighting the growing role of recombinant DNA technologies. In May 1985, University of California, Santa Cruz Chancellor Robert Sinsheimer hold "The Santa Cruz Workshop" on human genome sequencing. In March 1986, the DOE Office of Health and Environmental Research hold the "Genome Sequencing Workshop" in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to assess the feasibility of pursuing a Human Genome Project.

1988

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) assembles scientists, administrators and science policy experts to plan for a possible Human Genome Project. More +

1988

From Feb. 29 to March 1, 1988, NIH Director James Wyngaarden assembles scientists, administrators and science policy experts in Reston, Virginia, to lay out a plan for the Human Genome Project.

1988

The National Research Council Commission on Life Sciences and the U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment recommend a concerted genome research program. More +

1988

In April 1988, two published reports recommend creating an effort to sequence the human genome. The National Research Council Commission on Life Sciences, National Academy Press publishes "Mapping and Sequencing the Human Genome." The U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment publishes Mapping Our Genes—Genome Projects: How big? How fast?."

1988

NIH and DOE sign a memorandum of understanding to "coordinate research and technical activities related to the human genome." More +

1988

In October 1988, NIH and DOE sign a memorandum of understanding to "coordinate research and technical activities related to the human genome." Also, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) Otis R. Bowen creates the Office for Human Genome Research within the NIH Office of the Director James Wyngaarden.

1989

HHS establishes the National Center for Human Genome Research (NCHGR) with James D. Watson** as the first director. More +

1989

On Oct. 1, 1989, HHS creates the National Center for Human Genome Research (NCHGR) to carry out the NIH component of the United States Human Genome Project. The center's first director is James D. Watson, who co-discovered the double helical structure of DNA.

1989-1990

The NIH and Department of Energy each establish an Ethical, Legal and Social Implications (ELSI) Research Program. More +

1989-1990

At its January 1989 meeting, the Program Advisory Committee on the Human Genome establishes a working group to develop a plan for the ethical, legal, and social implications component of the human genome program. This working group, later named the NIH-DOE Joint Working Group on Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications of Human Genome Research (ELSI Working Group), holds its first meeting in September 1989. In January, 1990, the working group issue its first report. In it, the working group agrees that the ELSI program should anticipate and address the implications for individuals and society of mapping and sequencing the human genome.

1990

The Human Genome Project begins with an initial five-year plan. More +

1990

In April 1990, NIH and DOE publish a plan for the first five years of an expected 15-year project. The goals of the project include mapping the human genome and determining the sequence of all its 3.2 billion letters; mapping and sequencing the genomes of other organisms important to the study of biology; and developing technology to analyze DNA. On Oct. 1, 1990, the project officially begins. NIH allocates the first funds to research grants aimed at developing the scientific approaches, technologies, and resources needed to map and sequence the human genome.

1992

James D. Watson** resigns as the first director of NCHGR. More +

1992

On April 10, James Watson resigns as first director of NCHGR. NIH Director Bernadine Healy appoints Michael Gottesman, chief of laboratory of cell biology at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as acting NCHGR director.

1993

Francis S. Collins is appointed NCHGR director. More +

1993

On April 4, 1993, NIH Director Bernadine Healy appoints Francis S. Collins of the University of Michigan School of Medicine and Howard Hughes Medical Institute as director of NCHGR. Prior to that, Francis Collins led groundbreaking research identifying the genes responsible for cystic fibrosis, Huntingdon's disease, neurofibromatosis and other genetic disorders.

More

Francis Collins' Statement in Congress

1993

The Human Genome Project revises its five-year goals. More +

1993

Due to the rapid progress toward the goals established in 1990, NIH and DOE establish a new set of goals for the Human Genome Project in 1993 — two years ahead of schedule. The goals include creating detailed genetic and physical maps, developing efficient strategies for sequencing, and encouraging technology research through September 1998.

1994

Human Genome Project researchers publish a detailed genetic linkage map of the human genome. More +

1994

In September 1994, the Human Genome Project meets its first mapping goal — a comprehensive human genetic linkage map. Genetic linkage maps show the relative order of and approximate spacing between specific DNA patterns, called markers, positioned on chromosomes. This genetic linkage map met one of the project's scientific goals a full year ahead of schedule. Genetic linkage maps are the first tool that researchers use to find a disease-causing gene. These maps identify the general area of the chromosome that contains the gene.

1995

Human Genome Project researchers publish a physical map of the human genome. More +

1995

In December 1995, the project met one of the its goals is to complete a physical map that contains actual, physical locations of identifiable landmarks on chromosomes . A physical map uses sequence-tagged sites as the landmarks to help order large segments of DNA. The map in 1995 is a significant milestone toward that goal. The physical map serves as a backbone for ultimately assembling the full human genome DNA sequence.

1996

Bermuda Principles encourage open data access for the Human Genome Project. More +

1996

In February 1996, Human Genome Project leaders meet in Bermuda at the first International Strategy Meeting on Human Genome Sequencing. They decide that all human genomic sequence information should be made freely available and placed in the public domain within 24 hours of being generated by federally funded large-scale human sequencing centers. The "Bermuda Principles" are drafted to encourage research and development, and to maximize the Human Genome Project's benefits to society. This contrasts with the standard practice in scientific research of making experimental data available only after its publication. These principles reshape the practices of an entire industry and establish rapid prepublication data release as the norm in genomics and other fields. Project leaders reconvene in Bermuda the following year to affirm these principles at the second International Strategy Meeting on Human Genome Sequencing.

More

1997

NCHGR becomes the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). More +

1997

In January 1997, Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Donna E. Shalala signs documents that give NCHGR a new name and new status among other NIH research institutes. Secretary Shalala's statement on the renaming indicates that “designating the Center as an Institute will enhance the organization's image as an NIH focal point for studying and understanding human genetic disease and allow the NHGRI to operate under the same legislative authorities as the other NIH research institutes."

1998

The Human Genome Project sets new five-year goals. More +

1998

On Oct. 23, 1998, Science publishes the new NIH-DOE five-year plan for the Human Genome Project. Because all of the major goals of the previous five-year plan have been met, the new five-year plan predicts completion of human sequencing in 2003 — two years ahead of schedule. The plan reflects a commitment to generate a "working draft" of the human genome by 2001. It also notes that “because this [draft] sequence will have gaps, it will not be as useful as finished sequence for studying DNA features that span large regions or require high sequence accuracy over long stretches. Availability of the human sequence will not end the need for large-scale sequencing."

1999

The Human Genome Project successfully completes the pilot phase of sequencing the human genome. More +

1999

In March 1999, the international Human Genome Project successfully completes the pilot phase of sequencing the human genome and the launch of the full-scale effort to sequence all 3 billion letters that make up the complete genetic blueprint for a human.

1999

The International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium backs the rapid construction of a "working draft" sequence of the human genome and stands firm on open data access. More +

1999

In May 1999, following a meeting at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, leaders of the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium, comprised of 20 sequencing centers in the U.S. and around the globe, reaffirm their commitment to providing free, immediate and unrestricted access to human sequencing data. They also define powerful new ways to coordinate the worldwide effort to sequence the human genome. The group reiterates its commitment to place all sequence data in the public domain immediately and denounces the trend towards treating human genome sequence as a commodity.

1999

Human Genome Project researchers decode the DNA sequence of the first human chromosome. More +

1999

In December 1999, an international team of researchers achieves the scientific milestone of unraveling the genetic code of an entire human chromosome for the first time. Researchers decipher the sequence of the 33.5 million letters that make up the DNA of chromosome 22. Seeing the organization of a human chromosome for the first time at this level paves the way for the rest of the Human Genome Project.

More

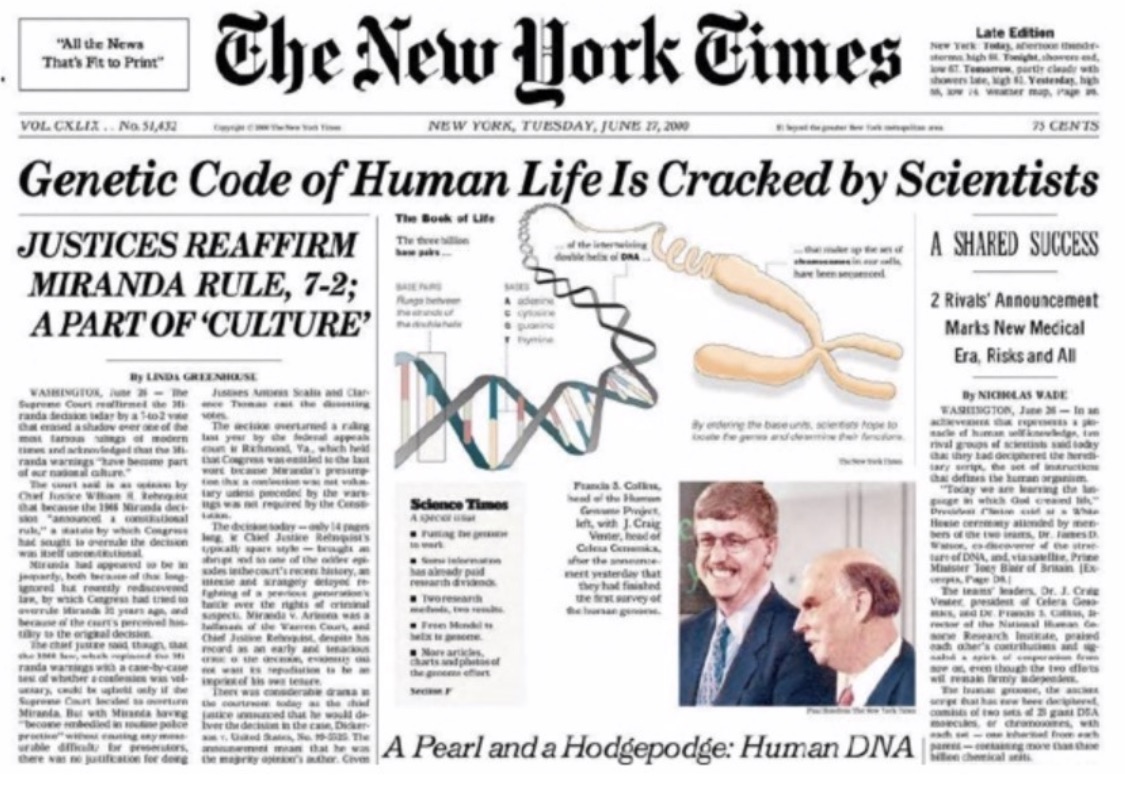

2000

The International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium announces the completion of a "working draft" human genome sequence. More +

2000

On June 26, 2000, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium announces that it completed a working draft of the sequence of the human genome — the genetic blueprint for a human being. President Bill Clinton holds a ceremony at the White House to announce this achievement. The ceremony takes place in the East Room of the White House, where politicians, ambassadors, scientists, company executives, disease advocates and journalists gather to celebrate a major milestone for the project.

More

Francis Collins' press conference notes

Francis Collins' notes for Bill Clinton

2001

The International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium publishes an initial analysis of the human genome sequence. More +

2001

On Feb. 12, 2001, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium announces the publication of a draft sequence and initial analysis of the human genome in the journal Nature. A wealth of information is obtained from the initial analysis of the human genome draft. For instance, the number of human genes is originally estimated to be about 35,000. (This is later revised to about 20,000.) Researchers also report that the DNA sequences of any two human individuals are 99.9% identical.

More

2003

The Human Genome Project is completed. More +

2003

On April 14, 2003, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium announces the successful completion of the Human Genome Project. This is more than two years ahead of schedule.

More

Letter of Congratulations from President Bush

House Resolution Designating April 2003 as “Human Genome Month”

2004

The International Human Genome Sequence Consortium publishes their finished human genome sequence. More +

2004

On Oct. 20, 2004, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium publishes its scientific description of the finished human genome sequence.

** James Watson was the first NHGRI Director and appears here as part of our history collection. Despite his scientific achievements, Dr. Watson’s career was also punctuated by a number of offensive and scientifically erroneous comments about his beliefs on race, nationalities, homosexuality, gender and other societal topics. Dr. Watson’s opinions on these topics are unsupported by science and are counter to the mission and values of NHGRI.

Last updated: July 5, 2022