The Big Picture

Appropriate use of population descriptors in research is a critical scientific issue that is important for advancing genomic science and improving healthcare across human populations. Thoughtful use by researchers and other stakeholders is important given the ethical, legal and social implications of their historical and current use.

- This explainer discusses and differentiates three common population descriptors — race, ethnicity and genetic ancestry — which are often used to distinguish groups of people participating in research and to inform some healthcare decisions.

- The inaccurate belief that human populations are biologically distinct has contributed to harms, such as justifying eugenics, promoting scientific racism, and marginalizing groups. In turn, misapplication of concepts of population groups has contributed to health disparities, alienated marginalized groups from research participation, and led to harmful stereotypes that have reinforced inequities.

- More work is needed to educate researchers, clinicians, policymakers and the public on the distinctions between race, ethnicity and genetic ancestry, and to advance the use of population descriptors in genomics and biomedical research.

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) assessed the methods, benefits and challenges in a review of the use of population descriptors in genomics research. The NASEM Report includes 13 recommendations designed to transform how population descriptors are used in human genetics and genomics research.

Explore this page

- What are population descriptors?

- Understanding genetic ancestry, race and ethnicity

- How well can researchers determine genetic ancestry?

- Are population descriptors social constructs?

- Why should researchers be intentional about how population descriptors are used in genomics research and health?

- Why does NHGRI care about this issue?

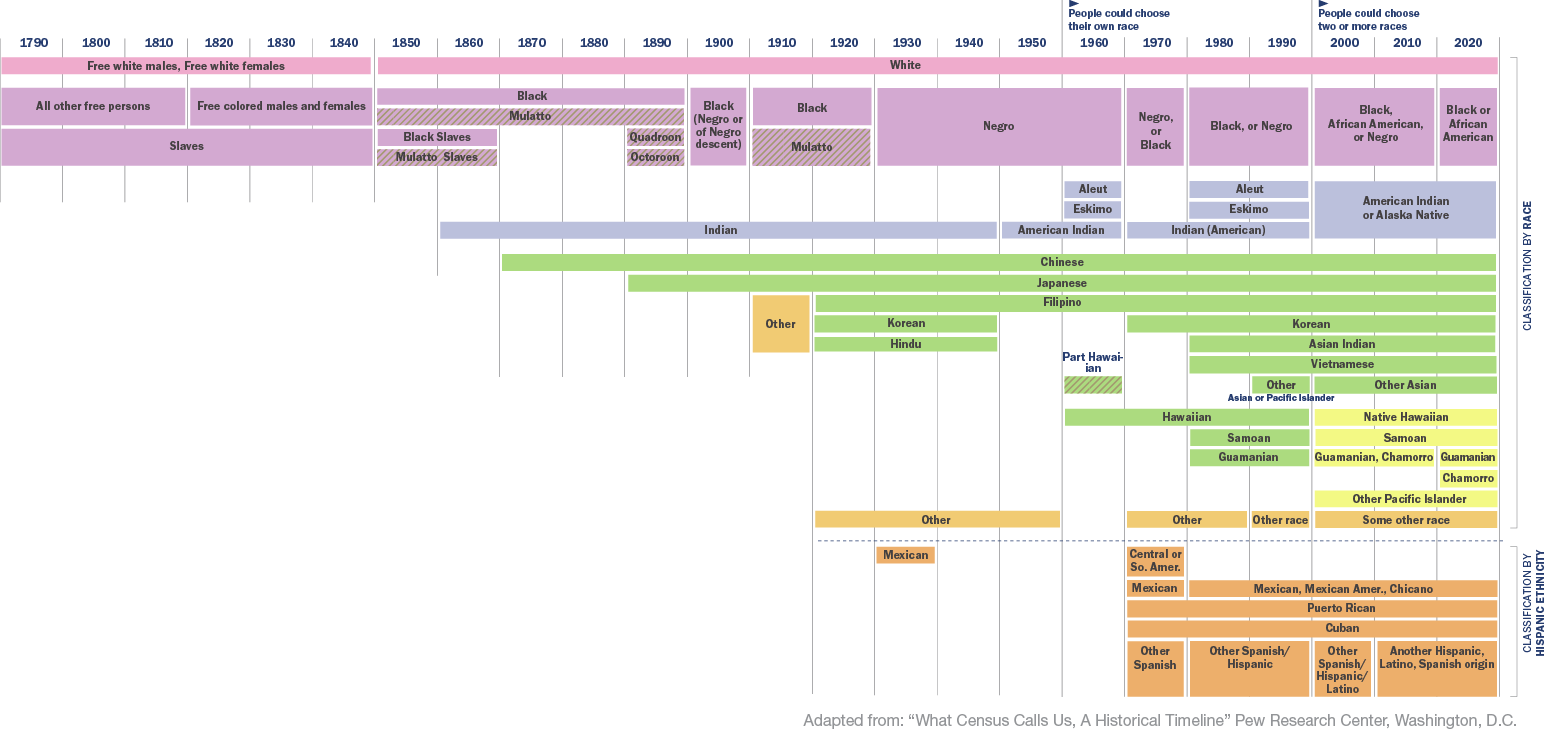

When the U.S. government established racial categories around 1790, they were tied to colonialism and flawed science. They were used in population surveys for purposes of taxation, government representation, counting enslaved persons and maintaining power.14 The names and number of categories changed over time due to shifts in scientific, political and social thinking about race and ethnicity.7

The major categories used in the U.S. 2020 Census15 included Hispanic, Latino or Spanish for ethnicity, and White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaskan Native and Asian or Pacific Islander.

In addition to their use in the census, race and ethnicity have been used to measure racial and ethnic health disparities and to track progress in lessening disparities. Race and ethnicity are also commonly used as a proxy.16 These uses may be helpful for research and public health, especially when other data are not available.

Advances in genomic medicine greatly amplify the urgency of ensuring the field exemplifies scientific and social accuracy in all of the work that we do. Simply stated, the design of some genomic research studies has exacerbated scientific flaws due to how data are being analyzed, interpreted, reported and aligned across data sets. In no small part, this is because of how we misuse population descriptors.

Race and ethnicity are not valid or reliable proxies for genetic ancestry. In addition, genetic ancestry is a poor proxy for the geographic area where someone is from, where they currently live or things that may be part of their surrounding environment. Relying on race, ethnicity or genetic ancestry as a proxy for something that is not measured in research often hides underlying biological, environmental or social factors that may contribute to health and disease. In healthcare, race and ethnicity have been improperly treated as biological or innate characteristics.

In society, there are real and measurable impacts of one’s racial or ethnic identity on health, wellness and status in the United States, whether self-identified or assigned by someone else. Thus, race and ethnicity may be useful for examining social or political issues; documenting racial/ethnic health disparities; examining the impact of racial bias in health service delivery17 and monitoring efforts within the biomedical workforce. Directly measuring and analyzing social determinants of health (SDOH), such as racism, violence, access to nutritious food or safe water, or exposure to trees and nature, would improve the rigor and usefulness of research. A growing collection of SDOH measures are available in a toolkit for researchers.18

In all types of research, when using population descriptors, researchers should be clear and transparent about which population descriptor(s) they are using, how they are measured and why they were chosen. Researchers should have a reasonable hypothesis for why specific descriptors may or may not be important to their research questions. Research should use labels and categories that accurately reflect what is being measured. Researchers should carefully consider whether race, ethnicity or genetic ancestry is the direct cause of the health differences we see across individuals or groups. If proxies are used in research because data of interest are not available or cannot be collected, then the challenges and limitations of doing so should be acknowledged.

The use of population descriptors in genomic and biomedical research is a critical scientific issue with varied ethical, legal and social implications (ELSI). NHGRI will continue its focus on this issue to promote the ethical, responsible and scientifically rigorous advancement of genomic science, genomic medicine and ELSI research. NHGRI is also focusing on this issue to:

- Recognize that people have been and continue to be harmed by the misuse of race in genomic research and the misinterpretation of research findings.

- Avoid repeating mistakes of the past, which has caused immediate and long-lasting harm to minoritized and disenfranchised groups, here in the U.S. and around the world.

- Earn the public’s trust by ensuring that researchers thoughtfully consider whether, when and how to use population descriptors; and ensuring that they are used in an ethical way.

- Build and maintain trust in science among those we hope will participate in genomic research.

- Ensure a more complete understanding of the diversity that exists across people who participate in research

- Ensure that all populations benefit from advances in genomic and biomedical research.

- Eliminate disparities in genomic medicine.

NHGRI strongly encourages researchers to move beyond population descriptors based on historic social constructs such as race and includes this shift as part of its “Bold Predictions for Human Genomics by 2030.” To help achieve these objectives, NHGRI supported The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) in its review and assessment of existing methods, benefits and challenges in the use of population descriptors in genomics research. The NASEM Report includes 13 recommendations designed to transform how population descriptors are used in human genetics and genomics research. Continued efforts are needed to implement and test the practices identified by the report. Ultimately, NHGRI’s goal is to strengthen the rigor and reproducibility of genetics and genomics research and produce discoveries that are broadly applicable and will benefit all.

Looking forward

Understanding the true role that genomics plays in health and wellness will require careful attention to the full spectrum of potential contributing factors, including genomic, biological or clinical traits; components of the natural, built or social environment in which people live; and larger systemic or structural issues. Clarity and specificity around population descriptors used in genomic research can improve the scientific integrity of research while also showing respect for the people represented in genomic research.

Last updated: October 24, 2024